1. Executive summary

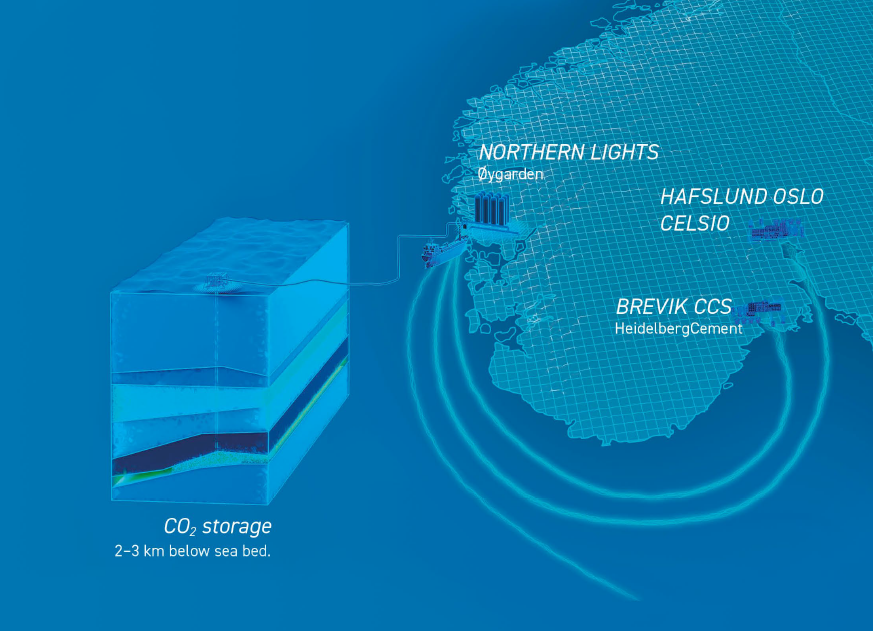

Longship is the first industrial CCS chain in construction under the current European legal framework, and until now, the only CCS chain where investment decisions have been made. Two CO2 capture projects and one CO2 transport- and storage project are being established under Longship.

“…Norway showed its leadership in Europe by making a major funding commitment to the Longship project. Longship will connect two different plants capturing CO2 in Norway with the Northern Lights storage facility deep under the North Sea. Northern Lights will be able to receive CO2 captured in neighboring European countries, as well, thereby playing an important role in meeting not just Norway’s ambitious climate goals but those of the entire region.”

CCUS in clean energy transition, International Energy Agency, 2020Gassnova’s role has been to ensure that the industrial partners are well-coordinated with each other and that the projects are developed in line with the states objectives. Through this “project integrator role” Gassnova has a thorough overview of the regulatory processes, issues and challenges Longship has encountered, and how these are resolved. With this report, Gassnova aims to provide information to subsequent CCS projects, public sector bodies and others who work to facilitate the use of CCS.

The Norwegian state provides state aid to the industrial partners Celsio (formerly Fortum Oslo Varme), HeidelbergCement and Northern Lights. The state will, according to the initial cost estimates, cover approximately 2/3 of the total costs01.

The commercial and regulatory framework for Longship is formed by several international conventions, EU and Norwegian legislation and the state aid agreements between the industrial partners and the Norwegian Government. The industrial partners therefore have to comply with many different laws and regulations and engage with a wide range of public sector bodies.

Norwegian public sector bodies are heavily involved in the development of the project and have different roles. Some of these – the regulatory roles – are well defined, though with limited experience in regulating CCS activities. In this report these roles are divided into three sub-categories: Regulator of HSE, Planning and Building Activities, Regulator of Resource Management and Safe Storage and Regulator of CO2 Emissions. The state has several agencies and directorates handling these regulatory roles in addition to municipalities and county governors. Other public sector roles originate from the fact that Longship is a “first-of-a-kind” project. These are divided into two sub-categories: The Project Integrator, described above, and the State Aid Provider.

In this report the regulatory issues and challenges facing Longship and how these are resolved are discussed in light of the state’s different roles.

The role Project Integrator targets the chicken and egg situation for CCS: No industry emitter will invest in a capture project without the existence of a storage solution, and no company will develop a storage site without knowing that there is CO2 to be stored.

Dividing the full CCS chain into separate subprojects; a capture and a transport/storage project, was a prerequisite for establishing a whole CCS chain and hence for investment decisions to be made. This allowed the emission source owners to develop their projects without having to establish their own transport and storage solution, and the transport and storage provider could develop its project independent of the capture projects. The state bears risks related to the interface between the projects.

To coordinate and facilitate the development of the CCS chain, it was important for the state to retain a “project integrator role”.

It has been important to manage interdisciplinary challenges and align different corporate cultures. The Longship CCS chain requires cooperation between different corporate cultures and practices. Different expectations concerning work processes, level of detail in deliverables, resource use, etc. are among these challenges.

Due to a lack of commercial incentives for the industrial partners, risks stemming from commercially immature solutions and immature regulatory frameworks, tailor made state aid agreements were needed.

As CCS was not commercially viable it was necessary to provide state aid to the industrial partners.

The high proportion of state aid makes it necessary for the state to follow up the projects to prevent undue distortive effects on competition and trade etc.

As the projects in Longship are first-of-a-kind, the project uncertainties are higher than would normally be encountered in well-rehearsed projects. The industrial partners therefore required cost sharing up to an agreed maximum level (related both to capital expenditure and operating expenses).

Northern Lights has identified a business case for the transport and storage of CO2: the state aid agreement gives Northern Lights incentives to enter into dialogue with potential customers across Northern Europe. Northern Lights’ potential future profits will be based on the tariff paid by potential new customers.

There are elements in the regulations that have been challenging for the industrial partners, such as lacking incentives for capture and storage of CO2 from biogenic sources. These are addressed through the state aid agreements.

The extensive share of state aid means that the industrial partners must comply with the comprehensive procurement procedures set out in the Act on Public Procurement. For some of the industrial partners this created a need to acquire new skills.

When regulating HSE, planning and building activities for a CCS chain, two main topics can be pinpointed: The risk associated with handling large volumes of CO2 and the risk associated with emissions from amines used in the capture process.

The HSE, planning and building regulation and related processes are generally “business as usual” for industrial partners and regulators. Emissions related to CCS are subject to the same legislation as other emissions.

Amine-based carbon capture produces small emissions of amines. Both Heidelberg Materials and Celsio have tested their capture technologies on their own flue gas. They both note that this has been important to reassure themselves that the amine emissions will not exceed certain levels and the degradation products will be below the limit set by the authorities.

Emissions previously released into air can shift to water as environmental recipient. This could pose some challenges for an updated emission permit. The temperature and volume of the emissions to water (cooling water from the CCS plant) are other issues that need to be taken into consideration.

A new regulation on safety and working environment for transport and injection of CO2 on the continental shelf has been developed by the Petroleum Safety Authority.

The interface between the regulatory agencies, the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (onshore regulator) and the Petroleum Safety Authority (offshore regulator), needed clarification in the case of intermediate onshore CO2 storage before transport through pipeline to permanent subsurface storage.

The industrial partners point out that it is important to involve local authorities early in the process due to the complexity and size of the projects.

The operator needs to secure a zoning plan and building consent for the pipeline from the quay out to one nautical mile offshore the baseline while petroleum pipes are exempt from this requirement. The transport and storage operators point out that this is a lengthy, resource intensive process and could possibly delay planning and execution.

Similarities and differences between the petroleum industry and the new CCS industry are discussed in light of regulating resource management and safe storage.

The licensing system for CO2 storage is operational and permits have been granted for Longship, being the first industrial CCS chain under the legal framework.

The licensing system for CO2 storage is similar to the licensing system for oil and gas exploration and production. The technologies and stakeholders are mainly the same for both industries, and the petroleum industry and the authorities are well acquainted with the licensing system for oil and gas. This is a clear advantage.

However, there are several important differences between the petroleum industry and the CCS industry. For instance, the business model for CCS (low market maturity, high risk, low return) is very different from the business model in the petroleum sector (high market maturity, high risk, high return). Due to these differences, some of the requirements under the current licensing system (third-party access, liabilities etc.) may make it challenging for the storage operator to handle risks and make investment decisions

A description of lessons learned related to the international regulation of CO2 emissions is given. Weak and lacking incentives for capturing and storing CO2, and barriers for CO2 chains across national borders are key words in this section.

Longship has highlighted the lack of climate regulations incentivising CCS in sectors not subject to EU ETS and for biogenic sources.

The EU ETS price signal was not sufficient to incentivise the industrial partners in Longship.

CCS relevant regulations have been applied to a CCS chain for the first time. Norwegian authorities have been in dialogue with the European Commission on their interpretation of the regulations.

Ship transport of CO2 is not subject to the EU ETS. A solution for the Longship project has been found through the arrangement between the industrial partners and the state. The regulations are under revision in the EU system, and a proposal for including all types of transport of CO2 for storage under the EU ETS is under consideration.

A measurement regime for CO2 in the CCS chain has been established. This is a prerequisite for transferring the responsibility for the CO2 between parties in a CCS chain.

National reporting of CO2 emissions, including captured and stored CO2 of biogenic origin, has been clarified in line with new international reporting rules.

A temporary solution for transporting CO2 across national borders for the purpose of offshore storage (the London Protocol) has been established. For Northern Lights to enter into a commercial agreement with an industrial partner outside of Norwegian borders, there must be a bilateral agreement between Norway and the home country of the emission source. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy is in dialogue with relevant countries with the aim of entering into bilateral agreements with key countries prior to Northern Lights’ injection start in 2024.

Applying the legal framework on an industrial CCS chain for the first time, requires practical clarifications and solutions. The requirements in the legal framework must correspond with the existing technical solutions and vice versa. For instance, measuring the amount of CO2 is a prerequisite for transferring the responsibility of the CO2 from one partner to another in the CCS chain. Always knowing who is responsible along the CCS chain is also a necessity.

The stakeholders involved in Longship all pinpoint trust between industry and the government as a prerequisite for the success of the project. The project is being realised even though some important regulatory issues are yet to be fully clarified. With a common goal of realising a CCS chain, all the stakeholders involved have, on the basis of this mutual trust, shown openness and flexibility.

Longship can already prove positive effects on the development of CCS in Europe. The existence of a CO2 transport and storage service provider like Northern Lights has removed an important barrier to CCS. Stronger climate policies and a higher ETS price have also contributed to an increased focus on CCS in key European industries. There has also been a development in the international and European legal framework since Longship was approved, and processes are ongoing.