4. Lessons learned

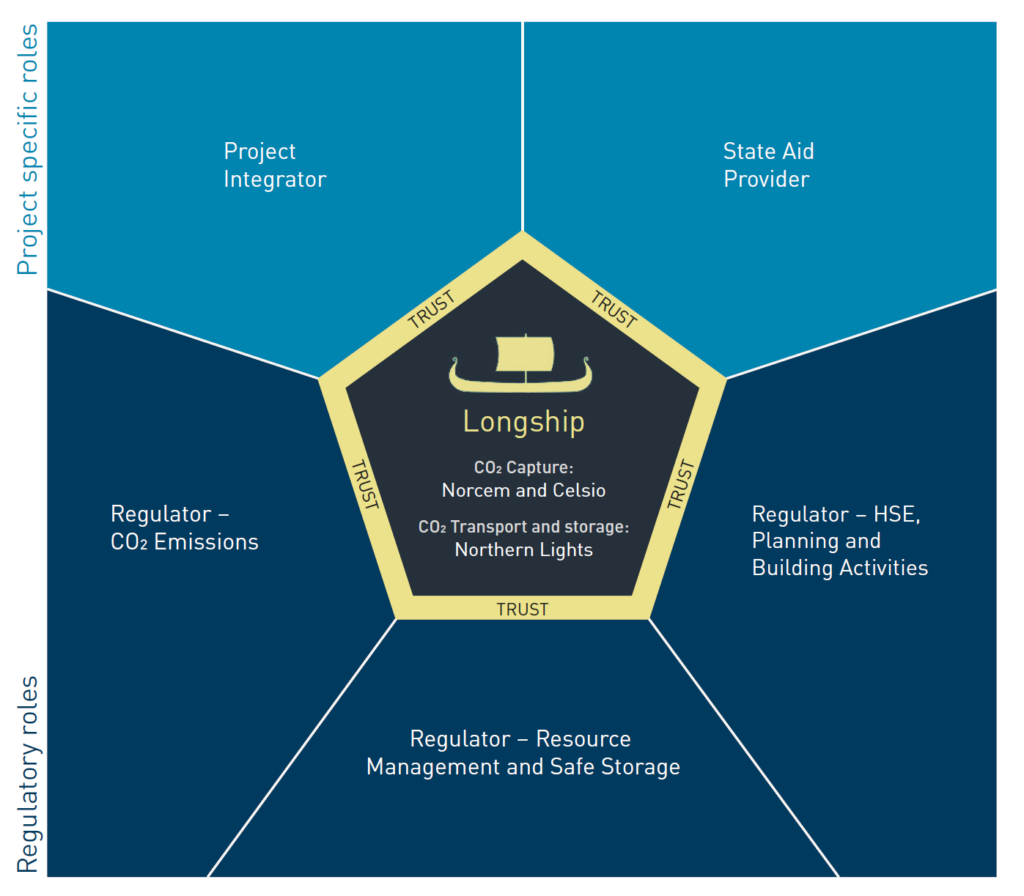

The industrial partners in Longship have to comply with many different laws and regulations and deal with a wide range of public sector bodies. In this section the regulatory issues and challenges and key learning points will be discussed in light of the state’s different roles.

Norwegian public sector bodies are heavily involved in the project development and have different roles. Some of these – the regulatory roles – are well defined. In this report these roles are divided into three sub-categories: Regulator of HSE, Planning and Building Activities, Regulator of Resource Management and Safe Storage and Regulator of CO2 Emissions. The state has several agencies and directorates handling these regulatory roles in addition to municipalities and county governors.

Other public sector roles originate from the fact that Longship is a “first-of-a-kind” project. These roles are divided into two sub-categories: the Project Integrator and the State Aid Provider. The Project Integrator is coordinating the three industrial partners and the Government.

Due to lack of commercial incentives for the industrial partners, risks stemming from commercially immature solutions and immature regulatory frameworks, there was a need for comprehensive state aid agreements. The state has no intention to copy these two roles to following CCS projects even though new CCS projects, in most cases, still will not be fully commercial. These projects have to seek financial support from established or new support mechanisms.

Longship consists of three individual projects: two CO2 capture projects (Heidelberg Materials’s project and Celsio’s project) and one CO2 transport and storage project (Northern Lights). Each industrial partner is responsible for planning, constructing and operating their own facilities even though the state provides financing and bears the risk related to the interface between the projects.

Heidelberg Materials and Hafslund Oslo Celsio have both selected amine technologies for their capture projects. Heidelberg Materials selected Aker Carbon Capture as capture technology provider with ACC solvent S26 at an early stage in the planning process, while Celsio selected Technip FMC as engineering contractor with Shell solvent DC103 before entering the FEED phase.

Northern Lights is owned by Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies. The three companies have worked as equal partners on the project since 2017, with Equinor as project lead. In 2021 the company Northern Lights JV DA was launched.

The CCS chain was initially split into the individual areas of capture, transport and storage after feedback from the industrial partners in the pre-feasibility phase. In early development the project consisted of three capture projects, one transport project and one storage project. One of the capture projects – Yara Porsgrunn – was discontinued in 2019.

The transport and storage projects were combined into a joint transport and storage project operated by Northern Lights after the concept phase. The CCS chain comprises different sectors and companies with very different corporate cultures. It was a prerequisite for the emission source owners to focus on the capture element alone, and the split of the CCS chain has also allowed the petroleum sector companies to focus on their core competences.

Gassnova has acted as a project integrator. The work done by the partners during the planning phase has been based on study agreements with Gassnova, but the degree of freedom given to the partners has been significant, and the various projects have been developed as the respective partners have seen fit. A technical committee with participants from the industrial projects and Gassnova has met on a regular basis to discuss topics of common interest (e.g. related to CO2 specification, export rates from the capture plants, use of loading arms between capture export terminal and ship, etc.). A committee for cross-chain operational aspects was also established (e.g. principles for developing the ship transport schedule, how to handle off-spec CO2 during loading of the ship, etc.)

This project integrator role has included responsibilities such as definition and follow-up of the studies throughout the project, including development of the design basis for the CCS chain, evaluation of deliveries from the partners after the concept study phase and the FEED study phase, including technical evaluation and ranking of the capture projects, developing and maintaining an overall project schedule and coordinating the development of the interfaces between these three projects, incl. management of a technical committee and an agreements committee. For a more in-depth account of lessons learned, refer to Gassnova’s report “Developing Longship – Key lessons learned”33.

Dividing the CCS chain into capture and transport/storage was a prerequisite for establishing a whole CCS chain and hence for investment decisions to be made. This allowed the emission source owners to develop their projects without having to establish their own transport and storage solution, and the transport and storage provider could develop its project independent of the capture projects. The state bears risks related to the interface between the projects.

To coordinate and facilitate the development of the CCS chain, it was important for the state to retain a “project integrator role”.

It has been important to manage interdisciplinary challenges and align different corporate cultures. The Longship CCS chain requires cooperation between different corporate cultures and practices. Different expectations concerning work processes, level of detail in deliverables, resource use, etc. are among these challenges.

Based on the Government’s ambition to realise an industrial CCS demonstration project, Gassnova, in cooperation with Gassco and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, carried out a pre-feasibility study in 2015. This study was carried out in cooperation with the industry. In addition to technical descriptions the study gave recommendations on how to overcome identified investment barriers.

The investment barriers identified for Longship (see table 02) have been overcome through a commercial negotiation process between the Ministry of Energy and Petroleum and each of the industry partners: Celsio, Heidelberg Materials and Northern Lights. This process has been conducted in parallel with the project maturation process.

In general, companies will make investments that continuously strengthen their competitiveness in relevant markets over time. Covering a part of the project cost is not sufficient to enable a project to be executed. The project also needs to make commercial sense to the industrial partner. It was therefore important for the industrial partners to have a strategic interest in their projects.

As described above, Longship consists of three individual projects: Heidelberg Materials’s capture project, Celsio’s capture project and Northern Lights’ transport and storage project. Each industrial partner is responsible for its own project, facility and sub-contractors, and the Government has entered into exclusive state aid agreements with each partner.

| Investments barriers (2015) | How this is solved in Longship |

|---|---|

| Low cost of CO2 emissions and lack of clarity of future climate policy | ■ State aid agreements that give certainty for cost coverage, up to a certain level (both OPEX and CAPEX). ■ Equal compensation for capturing CO2, whether the industry falls under the EU ETS or not, and regardless of the origin of the CO2 (fossil or biogenic) ■ State aid for phase 1 (capacity up to 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 per year) of the Northern Lights infrastructure. |

| Whole chain risk, related to the project development, to technical operation and the financial risk related other parties’ operations | ■ Pre-feasibility study concluded that the CCS chain should be split commercially, meaning that each industrial partner would have their own state aid agreement. Payment of state aid is based on each industrial partner’s own successful project (both in construction and in operation) ■ Gassnova acted as a project integrator: – Setting up a common project maturity process, with synchronised decision gates – Development of a common overarching design basis for the project, including CO2 specifications |

| Commercial and regulatory immaturity of the technology – Uncertainty related to cost and operation (yield) | State aid agreements reduce the project risk for industry. However, the state aid agreements require financial contributions from industry and full ownership of the installations and operations by the industrial partners. |

| CO2 capture (and CO2 storage) is not part of the core competence of most energy-intensive industries | Gassnova has for many years supported the development and aggregation of competence relating to CCS in Norway. Gassnova has evaluated the industrial projects at decision gates and given feedback to the industrial projects. However, the industry has taken full ownership and responsibility of its own projects. |

Table 02: Identified investment barriers for private CCS investments and how they are resolved for Longship.

The state aid agreements state that the Norwegian authorities will grant aid to Heidelberg Materials and Celsio to cover an agreed portion of the capture projects’ actual operating expenses and capital expenditure. At the same time, Heidelberg Materials and Celsio will have no costs for transport and storage of the CO2 captured the first 10 years of Northern Lights operations, according to the state aid agreements. The cost of realising and operating the transport and storage infrastructure is handled in the state aid agreement between the state and Northern Lights. Under this agreement, Northern Lights will cover some of the costs of transport and storage of Celsio’s and Heidelberg Materials’s CO2. In exchange, Northern Lights will get spare capacity in the transport and storage infrastructure for business development and as a basis for further expansions.

Because of the share of state aid granted (above 50 percent), the three projects become subject to the Act on Public Procurement34. Some of the industrial partners are not very familiar with this legislation.

The state aid agreements are intended to provide incentives for cost awareness to the industrial partners through cost sharing. Northern Lights also has an incentive for business development through the potential for profits if the market evolves. The state aid agreements compensate for differences in incentives for CO2 capture under different regulatory regimes, and for differences in incentives for bio-based and fossil CO2 capture. For further information, refer to Section 4.5.

As Norway is a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), the EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) has assessed and approved the three state aid agreements between the state and the industrial partners in Longship.35

As CCS was not commercially viable it was necessary to provide state aid to the industrial partners.

The high proportion of state aid makes it necessary for the state to follow up the projects to prevent undue distortive effects on competition and trade etc.

As the projects in Longship are first-of-a-kind, the project uncertainties are higher than would normally be encountered in well-rehearsed projects. The industrial partners therefore required cost sharing up to an agreed maximum level (related both to capital expenditure and operating expenses).

Northern Lights has identified a business case for the transport and storage of CO2: the state aid agreement gives Northern Lights incentives to enter into dialogue with potential customers across Northern Europe. Northern Lights’ potential future profits will be based on the tariff paid by potential new customers.

There are elements in the regulations that have been challenging for the industrial partners, such as lacking incentives for capture and storage of CO2 from biogenic sources. These are addressed through the state aid agreements.

The extensive share of state aid means that the industrial partners must comply with the comprehensive procurement procedures set out in the Act on Public Procurement. For some of the industrial partners this created a need to acquire new skills.

For the CCS chain, two main risk areas can be pinpointed: The risks associated with handling large volumes of CO2 and the risks associated with emissions from amines used in the capture process. For Heidelberg Materials, new process emissions to water (Heidelberg Materials has no emissions to water today) also needed to be handled. Different governmental agencies have the regulatory responsibility for different parts of the CCS chain.

All industrial activity is subject to the legislation on safeguarding, pollution control and building construction (among others). The permit regimes and processes are generally well known in the industry.

For Longship, the following Norwegian laws and regulations are the most relevant: the Pollution Control Act24, the Regulations on handling hazardous substances25, Regulations on major accident hazards36, the CO2 Safety Regulations26 and the Planning and Building Act27.

Celsio and Heidelberg Materials needed a consent from the Directorate for Civil Protection, the Labour Inspection Authority and the County Governor/Norwegian Environmental Agency. They also needed a building permit, a framework permit and an activity permit from the municipality. They have applied to Norwegian Environmental Agency for a permit under the Pollution Control Act24 and they need to apply for or update the ETS/quota permit.

Celsio holds a licence for the heating plants, boilers, and main pipeline networks to the outer geographical boundary. The expansion and conversion of the facilities requires a new licence. “Expansion and conversion” are defined as construction beyond the specifications given in the existing license. An impact assessment was also needed.

Heidelberg Materials, Celsio and Northern Lights have all conducted Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA). An EIA37 was not required for Heidelberg Materials’s CO2 capture project, but Heidelberg Materials wished to be transparent about its project with the authorities and their local community.

In order to establish a carbon capture and storage plant, Celsio needed a new zoning plan according to the Planning and Building Act27. As a part of this, an EIA38 was required.

For Northern Lights the EIA39 was required under the several regulations, among others: the Storage Regulations21, the Planning and Building Act27, and the Pollution Control Act24.

CO2 differs from hydrocarbons in many ways, and it is important to note that it does not ignite like hydrocarbons. There is therefore no risk of explosion due to ignition. CO2 is not harmful to living organisms in low concentrations. HSE risks are linked to overpressure and leakage of large volumes. Leakage of large volumes with high concentrations of CO2 is harmful to most living organisms, humans included, and should be avoided or, in the worst case, mitigated without delay.

The Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection regulates facilities handling of hazardous substances, including pressurised CO2, and has provided necessary consents to the industrial partners in the Longship project. The Petroleum Safety Authority has the regulatory responsibility for safety, the working environment, emergency preparedness and security in the petroleum sector. The Petroleum Safety Authority has developed new regulations on safety and working environment for transport and injection of CO2 on the continental shelf (the CO2 Safety Regulations26).

During the planning of the transport and storage infrastructure it became apparent that it was not clear where the responsibility of the Directorate for Civil Protection stopped and that of the Petroleum Safety Authority started. With regard to intermediate storage of CO2 onshore before transport in a pipeline for permanent storage in a reservoir under the seabed, the Directorate for Civil Protection and the Petroleum Safety Authority have generally agreed on the following:

The Directorate for Civil Protection is the authority responsible for the handling of CO2 on land, both at the capture facilities and in the intermediate storage before transport in a pipeline. The Petroleum Safety Authority is responsible for transport in the pipeline from upstream of the export pump, which includes the necessary equipment and piping systems for operation and maintenance of the pipeline, as well as equipment and systems for well monitoring and control and associated emergency and safety systems in connection with pipeline and injection well. However, this is an interface that can be complicated for the reception facilities. There may therefore be a need for case-by-case assessments of where the interface should go40.

An amine-based CO2 capture plant will produce small amounts of amine emissions to air. Amines can react with other substances in the atmosphere and form nitrosamines and nitramines. Some nitrosamines and nitramines have shown carcinogenic effects in animal studies, so any spread in the environment is not acceptable and should be limited. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health has given recommendations for how much nitrosamine and nitramine can be allowed in the air and in drinking water. This has given the Norwegian environmental authorities a method for setting emission limits for CO2 capture plants. The method for documenting emissions is based on a specific model developed for the emitting sites. This is due to the complex atmospheric chemistry, dispersion patterns and emission components of each site. The selected CO2 capture technologies at the two capture sites have provided documentation on specific performance related to CO2 capture, solvent degradation and potential solvent emissions to air from previous test sites. Documentation on these parameters for specific flue gases from a cement plant and a waste-to-energy plant were not available. Both of the capture sites therefore ran a pilot test campaign on the selected technology on site to document that the technology was fit for purpose and would meet the stringent emission requirements when exposed to the specific flue gas.

An added chapter (35, 7a) in the Pollution Regulations22 is intended to ensure that all storage of CO2 is done in an environmentally safe way. All companies that inject and store CO2 need a permit from the Norwegian Environmental Agency. For further information refer to Section 3.1.1.

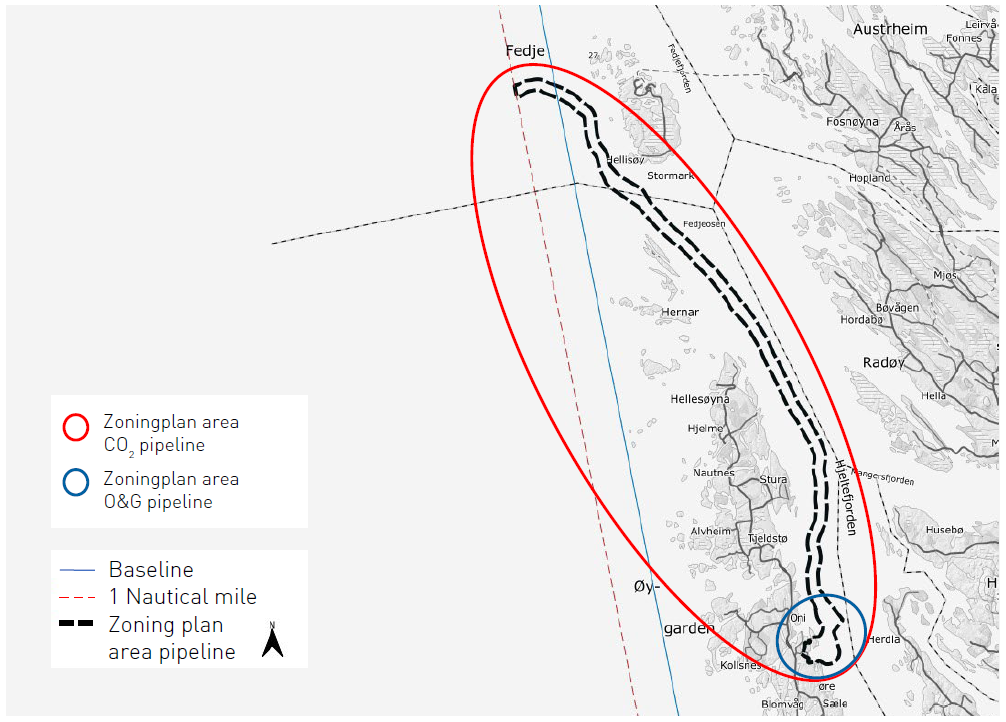

According to the Planning and Building Act27, the operator needs to obtain a zoning plan and building consent for the pipeline from quay out to one nautical mile offshore (the baseline – Norwegian “grunnlinje”). For the Longship project this involves applications to two municipalities and agreement with many stakeholders (e.g. crossing pipelines and infrastructures). This is a lengthy process which ties up resources and could possibly delay planning and execution.

Petroleum pipes are exempt from these requirements in the Planning and Building Act27, Chapter 3, Section 1-3. This exemption applies from the quay and further offshore, not on the land facilities. Figure 03 indicates the difference in zoning plan area for petroleum and CO2 pipelines. Northern Lights have initiated contact with relevant Ministries to address the difference in requirements for CO2 pipelines vs petroleum pipelines.

For the CCS chain, two main risk areas can be pinpointed: The risk associated with handling large volumes of CO2 and the risk associated with emissions from amines used in the capture process. The HSE, planning and building regulation and related processes are generally “business as usual” for industrial partners and regulators. Emissions related to CCS are subject to the same legislation as other emissions.

Amine-based carbon capture produces small emissions of amines. Both Heidelberg Materials and Celsio have tested their capture technologies on their own flue gas. They both note that this has been important to reassure themselves that the amine emissions will not exceed certain levels and the degradation products will be below the limit set by the authorities.

Emissions previously released into the to air can shift to water as the environmental recipient. This could pose some challenges for an updated emission permit. The temperature and volume of the emissions to water (cooling water from the CCS plant) are another issue that one needs to be taken into consideration.

A new regulation on safety and working environment for transport and injection of CO2 on the continental shelf has been developed by the Petroleum Safety Authority.

The interface between the regulatory agencies the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (onshore regulator) and the Petroleum Safety Authority (offshore regulator) needed clarification in the case of intermediate onshore CO2 storage of before transport through pipeline to permanent storage in a reservoir under the seabed.

The industrial partners point out that it is important to involve local authorities early in the process due to the complexity and size of the projects.

The operator needs to secure a zoning plan and building consent for the pipeline from the quay out to one nautical mile offshore the baseline while petroleum pipes are exempt from this requirement. The transport and storage operators point out that this is a lengthy process binding resources and could possibly delay planning and execution.

A CCS-specific regulatory framework, to ensure safe long-term storage for CO2, was implemented in Norway in 2014, through the implementation of the EU CCS Directive19. For the Norwegian implementation of the EU CCS Directive19, a two-track system was chosen41. The system separates industrial CCS from CCS related to petroleum activities. The two sets of CCS activities are regulated under different acts and regulations, as the objectives of the parallel systems are different. The main objective of the petroleum activities is to ensure that resource management is “carried out in a long-term perspective for the benefit of the Norwegian society as a whole”, i.e. value creation for the whole of society. The objective of CO2 storage as formulated in the regime for industrial CCS is related to mitigating climate change and it must “contribute to sustainable energy generation and industrial production, by facilitating exploitation of subsea reservoirs on the continental shelf for environmentally secure storage of CO2 as a measure to counteract climate change”.

Industrial CCS is regulated in the Storage Regulations21 (Section 3.1). The Storage Regulations21 are subject to the Act on other underwater natural resources42. The Longship project is defined as an industrial CCS project subject to the Storage Regulations21.

The Storage Regulations21 govern issues related to safe geological storage of CO2. The climate and environmental aspects of storage are regulated by the environmental authorities through a new chapter in the Pollution Regulations22 (Sections 2.1 and 3.4).

The system for obtaining permits for subsurface geological storage of industrial CO2 is similar to the petroleum licensing system. The permit system consists of a set of permits and obligations which the operator is subject to and needs to obtain and fulfil during the time frame of the project: pre-operation, operation, cessation of operation (decommissioning), and transfer of liability to the Norwegian state. For more information on the permit system refer to Section 3.1.1.

The companies involved in CO2 storage are energy companies with extensive oil and gas experience. The technologies used for CO2 storage and the competences involved are generally the same as for oil and gas activities. The permit regime for oil and gas is of course familiar to these industries and the authorities, which is an advantage.

The authorities have to safeguard the companies’ legal rights and also safeguard the interests of society by preventing monopoly situations, protecting the environment etc.

The transport and storage component of Longship, Northern Lights, is a joint venture partnership between Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies. Northern Lights JV DA was established and incorporated in February 2021, but the partnership was formed back in 2017.

In 2019 the authorities granted Equinor, on behalf of the Northern Lights consortium, a permit to exploit an area for CO2 storage on the Norwegian continental shelf (EL001). The permit was later transferred to Northern Lights. Northern Lights’ plan for development, installation and operation (PDO/PIO), including an Environmental Impact Assessment, was approved by the authorities in 2021. Before the start of operation Northern Lights will need a permit for injection and storage of CO2. Northern Lights plans to send the application for this permit to the Norwegian Environmental Agency during the autumn of 2022. To obtain the injection permit, a full monitoring plan must be submitted beforehand. This will also need approval from the EFTA Surveillance Agency. For more information refer to Section 3.1.1.

In April 2022 the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy awarded two new licences in accordance with the Storage Regulations21 on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS), one in the North Sea and one in the Barents Sea. The licence in the North Sea has been awarded to Equinor ASA, while the licence in the Barents Sea has been awarded to Equinor ASA, Horisont Energy AS and Vår Energi AS43.

The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE) has also proposed changes44 to the Company Act45 and the Storage Regulation21. If approved, the MPE argues that these changes will contribute to simplification for the concerned companies. In its consultation response Northern Lights pinpoint the differences between the petroleum industry and the CCS industry and argue for a comprehensive review of the legal framework for CCS as a new and upcoming business area.

Making Longship investable for the storage operator:

Before the transport and storage operator Northern Lights decided to invest in the transport and storage infrastructure, they expressed some concerns about the perceived uncertainty relating to future permits and how the state would enforce the legal framework.

In general, there are provisions in the Storage Regulations21 that imposes uncertain future liabilities and other obligations on the storage operator. The uncertainty is related to different parts of the Storage Regulations21, including: Monitoring (Section 5-4), Transfer of responsibility to the state (Section 5-8), Financial security (Section 5-9), Financial mechanism (Section 5-10) and Third-party access to facilities for storage of CO2 and storage sites (Section 5-12).

The perceived uncertainty was related to a lack of experience of how the CCS-specific regulations would be enforced, especially related to when, and the conditions for, transfer of the responsibilities under the Storage Regulations21 to the state, demands for monitoring, the amount and form of the financial security that would have to be provided before injection could start, the amount to be provided through the financial mechanism before transfer of responsibility at the end of the license, and the requirements for obtaining an injection permit in general.

The business model for CCS (low market maturity, high risk, low return) is very different from the business model in the petroleum sector (high market maturity, high risk, high return). In short, the storage operator was of the opinion that the Storage Regulations21 gave too much uncertainty in their business model.

An example of how a provision in the Storage Regulations21, seen from the transport and storage partner’s perspective, places risk on the transport and storage partner, is the requirement for third-party access to the storage infrastructure and the lack of control of the conditions for this. The state argues, however, that requirement for third-party access only will come into play if the storage operator do not need the infrastructure itself, and if third party access is required, the operator will be financially compensated.

For a financial investment decision to be made by Northern Lights, the state needed to bear a substantial part of the risk, as well as granting investment and operating aid to cover a portion of Northern Lights’ costs (for more information about the state aid agreement, refer to Section 3.2). The State’s liability also covers part of the risk for a potential but unlikely leakage from the subsurface storage complex once the CO2 from Heidelberg Materials and Celsio is stored. Northern Lights’ liability for any leakage of CO2 received from Heidelberg Materials and Celsio during the operating period, is limited to a maximum ETS price of EUR 40 per tonne (index adjusted).

This was agreed at a time when the EU ETS price was approximately EUR 20 per tonne. The Norwegian authorities will, subject to certain conditions, also grant closure support for eligible removal costs. Closure support is only relevant for CO2 storage given the legal requirements pertaining to the administration of such sites. A minimum monitoring period of 20 years applies46 before the responsibility is transferred to the state.

As well as providing risk relief to Northern Lights through the state aid agreement, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy in 2020 (prior to the Northern Lights’ final investment decision) sent a “comfort letter”47 to the transport and storage operator (Equinor ASA) confirming the state’s common goals with the industry, and the intention to find and implement appropriate solutions to the above, raised concerns.

The licensing system for CO2 storage is operational and permits have been granted for Longship, being the first industrial CCS chain under the legal framework.

The licensing system for CO2 storage is similar to the licensing system for oil and gas exploration and production. The technologies and stakeholders are mainly the same for both industries, and the petroleum industry and the authorities are well acquainted with the licensing system for oil and gas. This is a clear advantage.

However, there are several important differences between the petroleum industry and the CCS industry. For instance, the business model for CCS (low market maturity, high risk, low return) is very different from the business model in the petroleum sector (high market maturity, high risk, high return). Due to these differences, some of the requirements under the current licensing system (third-party access, liabilities ect) may make it challenging for the storage operator to handle risks and make investment decisions.

There are several laws and regulations (international and national) that form the basis for the climate regulations in Norway (Section 3.1).

Heidelberg Materials’s CO2 emissions are covered by EU ETS, but Celsio’s CO2 emissions are not. As from 01.01.2022, both Heidelberg Materials and Celsio are subject to a new national combustion tax. Both emission sources have CO2 stemming from both fossil and biogenic sources. CO2 emissions based on sustainable biogenic sources do not need to be compensated by EU ETS allowances.

Longship has highlighted the lack of regulation for CCS in sectors not subject to EU ETS and for biogenic sources. Also, for Heidelberg Materials the ETS price signal was not sufficient to incentivise the company to make an investment decision without financial support. The ETS price was somewhere between 20 and 30 euros when the state aid agreements were negotiated in 2019-2020. At the time Celsio had no economic incentive to cut its emissions.

The industrial partners in Longship have to report their CO2 emissions to the Government. For the industrial partners subject to the EU ETS the ETS Directive16 and the EU Monitoring and Reporting Regulation20 is relevant.

The fact that ship transport is not subject to EU ETS had implications for the possibility of transferring responsibility for the CO2 in the CCS chain. For Longship this has been solved through the state aid agreements.

Norway, as a country, is required to monitor its emissions under the EU’s Climate Monitoring Mechanism, which sets the EU’s own internal reporting rules based on internationally agreed obligations. In Longship CCS relevant regulations have been applied on a CCS chain for the first time. Norwegian authorities have been in dialogue with the EU Commission on their interpretation of the regulations. For more information refer to Section 5.1.

In addition to the EU, Norway has to report GHG emissions and removals to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. GHG emissions are reported to the UN in a set of common reporting format (CRF) tables. A shortcoming of the CRF tables has been that it is difficult to transparently report carbon capture and storage (CCS) of biogenic CO2 and have this reflected in the national totals. At the COP26 in Glasgow the CRF tables were improved. CCS of biogenic CO2 can now be reported in line with CCS of fossil CO2, both to EU and to the UN.

The London Protocol14 also poses some challenges for cross-border CCS. The London Protocol14 contains a prohibition on export of all waste and other matter to other states for dumping or incineration at sea. In 2009, the parties to the Protocol adopted an amendment that allows for the export of CO2 to other states for storage purposes under certain conditions. This amendment will enter into force when ratified by two-thirds of the 53 parties. This is a legal obstacle to cross-border cooperation on CCS. As of February 2022, only nine of the 53 Contracting Parties – Norway, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Finland, Estonia, Sweden, Denmark and South Korea have formally accepted the amendment.

In 2019, the parties to the London Protocol14 supported a Norwegian–Dutch proposition to allow provisional application of this amendment while awaiting ratification by two-thirds of the 53 parties. Countries that so wish can make arrangements for the transport of CO2 across national borders by submitting a declaration to the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

This has implications for Northern Lights’ business development. Bilateral agreements between Norway and the relevant countries need to be in place for cross-border transport of CO2 to take place. This activity is led by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. Informal consultations have started with a number of European countries. Memorandums of understanding on CCS collaboration have been signed with Belgium and the Netherlands.

Longship has highlighted the lack of climate regulations incentivising CCS in sectors not subject to EU ETS and for biogenic sources.

The EU ETS price signal was not sufficient to incentivise the industrial partners in Longship.

CCS relevant regulations have been applied to a CCS chain for the first time. Norwegian authorities have been in dialogue with the European Commission on their interpretation of the regulations.

Ship transport of CO2 is not subject to the EU ETS. A solution for the Longship project has been found through the arrangement between the industrial partners and the state. The regulations are under revision in the EU system, and a proposal for including all types of transport of CO2 for storage under the EU ETS is under consideration.

A measurement regime for CO2 in the CCS chain has been established. This is a prerequisite for transferring the responsibility for the CO2 between parties in a CCS chain.

National reporting of CO2 emissions, including captured and stored CO2 of biogenic origin, has been clarified in line with new international reporting rules.

A temporary solution for transporting CO2 across national borders for the purpose of offshore storage (the London Protocol14) has been established. For Northern Lights to enter into a commercial agreement with an industrial partner outside of Norwegian borders, there must be a bilateral agreement between Norway and the home country of the emission source. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy is in dialogue with relevant countries with the aim of entering into bilateral agreements with key countries prior to Northern Lights entering into operations in 2024.

The Nordic region is regarded as a world leader when it comes to trust among its population48. A high level of trust is an important resource for a society.

The stakeholders involved in Longship all pinpoint trust as a prerequisite for succeeding with the project. The project is being realised even though important regulatory issues have yet to be clarified and it is unclear how the authorities will enforce the regulations. For more information, refer to Section 4.4.

The project has been developed through a phased project development process, with several decision gates for both industry and the state. Gassnova believes that this approach has been instrumental in gradually building trust between the public and private sector before final investment decisions were made. During the project development process both the industrial projects and the state aid agreements has been matured.

In view of the state’s and industry’s common goal of realising a CCS chain, all the parties have shown an openness and flexibility that is not common for other projects.

“What we set out to achieve, well over a decade ago, is now turning into reality. It is a strong result of a fruitful collaboration between [all stakeholders] across the CCS value chain in Norway.”

(Giv K. Brantenberg, General Manager HeidelbergCement Northern Europe, from the Northern Lights summit 2022)