3. Regulatory and commercial framework

Norway’s regulatory framework and policies on climate change, energy and environment are largely defined, influenced or inspired by international agreements and policies.

International frameworks such as the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) outline the conditions for mitigating climate change.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) provides guidelines for how national GHG inventories should be prepared and has decided on how the GHG inventories should be reported under the Convention, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. This sets the framework for national GHG emissions accounting. The GHG emissions and removals are reported to the UNFCCC in a set of common reporting format (CRF) tables.

Another international convention particularly relevant to the Longship project is the London Protocol14 which regulates the prevention of marine pollution and stipulates certain requirements to the export of CO2 for the purpose of sub-seabed geological storage.

Norway is not a Member State of the European Union (EU). However, it is associated with the Union through its membership of the European Economic Area (EEA) and is therefore an equal partner in the Single Market, on the same terms as the EU Member States. EU regulations and directives are implemented in Norwegian law as committed to in the EEA agreement.

The EU will contribute to achieving the Paris Agreement through three “pillars”. Norway is involved in all three pillars15 of EU climate policy:

■ The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) which regulates emissions from manufacturing industry, power and heat generation, petroleum, and aviation through the EU ETS Directive.16

■ The Effort Sharing Regulation for non-ETS emissions17: this assigns each country a binding target for reducing emissions from transport, buildings, agriculture, waste, and some emissions from the oil and gas industry and industrial production.

■ The Land-Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) Regulation18: the Regulation sets out accounting rules for uptake and removals of CO2 in the LULUCF sector. The legislation lays down an obligation to ensure that overall greenhouse gas emissions from land use and forestry do not exceed removals (this is known as the ‘no-debit’ rule).

The CCS Directive19, the ETS Directive16 and attaching regulations are particularly relevant to the Longship project. The CCS Directive19 is the legal framework for environmentally safe geological storage of CO2 underground, aimed at stabilising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, and the ETS Directive16 is mentioned above.

The EU ETS Monitoring and Reporting Regulation20 lays down rules for monitoring and reporting GHG emissions and activity data pursuant to the EU ETS Directive16. Article 49 deals with CO2 that is captured in an ETS installation and transferred out of the installation.

The above-mentioned CCS Directive19 was implemented in Norwegian law in 2014 via the Storage Regulations21, an added chapter in the Pollution Regulations (Chapter 35 (7a))22 and an added chapter in the Petroleum Regulations23 (4a).

Other relevant Norwegian laws and regulations are the Pollution Control Act24, the Regulations on handling hazardous substances25, the CO2 Safety Regulations26 and the Planning and Building Act27.

The Norwegian state’s obligation to secure the best possible utilisation of common resources, pollution control and a safe working environment is the logic behind a licensing regime for industrial activities in general, and hence also for a CCS chain. To operate a CCS chain, the industrial partners need several permits.

This Section lists and explains the specific permits, licences and consents (here collectively called permits) needed to establish and operate a CCS chain in Norway, focusing on the storage domain of the whole chain. The reason for this is that the licensing system related to capture of CO2 is almost the same as for industrial activities in general (refer to Section 4.3), and ship transport of CO2 is regulated in the same way as ship transport of other liquefied gases.

The laws and regulations governing the different permits are listed in the summary of this report and a table listing the different storage-related permits28 are found in Appendix A.

Note that the following applications and permits could be processed/approved simultaneously or in slightly different order than listed, but this gives a general outline. Also note that most applications to the governmental authorities are also subject to consultation rounds, and all planned activities are required to conduct a thorough Environmental Impact Assessment. As a consequence of this it is important to consider the stakeholder engagement in the permit processes and ensure that all steps in the process are followed up thoroughly.

Below the different licences and permits required are described briefly (refer to Appendix A for a status on the different permits in Longship):

Prior to applying for any of the offshore licences related to geological storage, operators are free to screen the Norwegian continental shelf for possible storage sites. Screening does not require a licence from the authorities. Access to existing, publicly available datasets (seismic data, electromagnetic data, well data etc.) can be bought and used as a basis for future applications for the different permits listed below. The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate has compiled CO2 atlases for the Norwegian offshore regions. These atlases and the available datasets for Norwegian Continental Shelf are comprehensive and of very high quality, ensuring high quality screening processes.

The survey licence (Storage Regulations21, Chapter 3) may be granted to several operators at the same time and is valid for one or more geographically defined areas (called blocks or parts of blocks). The licence covers geological, petrophysical, geochemical and geotechnical activity, and shallow drilling may also be permitted. All these activities must be reported to the responsible authorities prior to the activity.

The exploration licence (Storage Regulations21, Chapter 4) gives exclusive rights for investigations to the licensee. If there is a consortium, one of the companies will be named as the operator. The investigation licence is valid in one or more blocks or parts of blocks and includes a work commitment. This commitment might include exploration well(s) and seismic surveys with details specified by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. Drilling of wells or other activities that might affect the environment must be permitted by the Norwegian Environmental Agency (Pollution Control Act24, Section 11, and Petroleum Safety Authority gives consent).

The exploitation licence (Storage Regulations21, Chapter 5) will be awarded to one licensee (which may be an enterprise consisting of more than one body corporate). An applicant holding an exploration licence in the specific area will be preferred if the work commitments are fulfilled. Only one operator will be appointed per storage location. If the licensee consists of multiple bodies corporate operating as a joint venture, one of the participants will be named as the operator. The application for an exploitation licence for a sub-seabed reservoir for injection and storage of CO2 must be sent to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. The exploitation licence allows for the use of the geological resource (reservoir) as a storage site but does not allow for injection and storage of CO2 into the reservoir.

An injection and storage permit falls within the remit of the Norwegian Environmental Agency and must be applied for separately and closer to the start of injection (see next paragraph). If the licensee decides to develop the subsea reservoir for injection and storage of CO2, they must submit a plan for development and operation (PDO) including a plan to install and operate the facilities related to transport, receival and storage of CO2 (PIO) and an Environmental Impact Assessment (Storage Regulations21, Sections 4.5 and 6.1). After the plans and the Environmental Impact Assessment have been approved by the authorities (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, consent issued by Petroleum Safety Authority) the licensee must make its final investment decision.

An injection and storage permit (Pollution Control Regulations22, Section 35-4) allows for injection and permanent storage of CO2 in the stratigraphic layers elaborated in the exploitation permit and is issued by the Norwegian Environmental Agency. A letter of consent must be issued by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy/Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, the Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion and Petroleum Safety Authority. The Petroleum Safety Authority gives consent according to the (CO2 Safety Regulations26, Section 12). These regulations concern safety and the work environment relating to CO2 storage on the continental shelf.

Along with the injection and storage permit, the transport and storage operator must have a CO2 emission permit from the Norwegian Environmental Agency (Pollution Control Act24, Section 11) for potential emissions of CO2 from the storage and transportation facilities. A yearly report of emissions (in the event of leakage) is required by law (Greenhouse Gas Emission Trading Act29, Section 16), and the operator will need to surrender enough allowances to cover its emissions.

The storage operator also needs an emission permit for the deployment of pipelines to the storage complex (Pollution Control Act24, Section 11). The Norwegian Environmental Agency also issues this permit. The operator is also required to obtain a zoning plan and building consent for the pipeline from the quay out to sea; this is regulated by the Planning and Building Act27

The process described above is not fully applied for Longship. The reason for this is among others that CO2 storage is a new business area with new regulations.

Screenings of areas in the North Sea for storage suitability were done by Gassnova and Equinor (then called Statoil) in connection with the planned (and later abandoned) full scale project at Mongstad. After the screening process, two areas, Aurora and Smeaheia, were chosen as promising prospects. The Aurora and the Smeaheia prospects were then subject to a maturation process, where the Aurora prospect was matured to a high level. Smeaheia was initially selected as CO2 storage complex, but this was later changed to the Aurora prospect30, which was matured to such a level that the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy/Norwegian Petroleum Directorate accepted an application for an exploitation licence directly. Hence, the survey licence and the exploration licence were not applied for in the process. The Northern Lights Joint Venture was founded as a result of three companies being awarded exploitation licences for Aurora. For Longship the injection and storage permit and permits related to CO2 emissions and emissions from pipeline are yet to be issued.

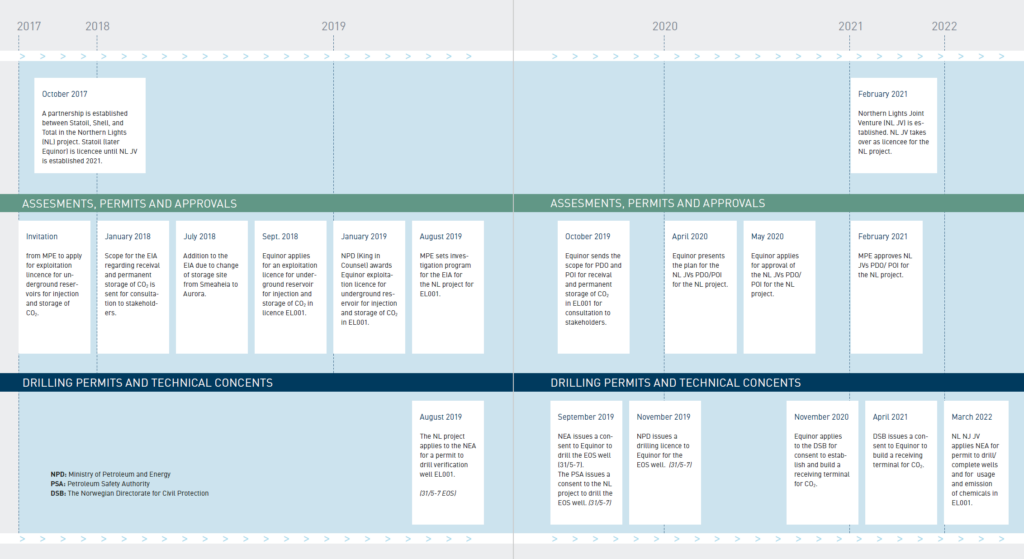

This Section has focused primarily on the regulations and permits up to the current status of the Longship project (Q2 2022) and a timeline of the storage relevant licences and permit are shown in figure 01. CO2 storage is a long-term commitment with regulations and permits reaching far into the future. One of these concerns the monitoring of the storage site (refer to Section 5.3).

(assessments, permits and concents)

Northern Lights, Heidelberg Materials and Celsio have been incentivised by state aid agreements, supplementing the EU ETS price and a recently implemented national combustion tax. In this section the original state aid agreements, concluded in 2020, is described. Celsio has recently finalized (June 2022) the agreement with the state after securing additional financing. The text in this report may not fully cover the new agreement.

The CCS chain is split commercially, meaning that each industrial partner has its own state aid agreement. Payment of state aid is based on each industrial partner’s own successful project, in both the construction and the operation phase. The state aid agreements give certainty for cost coverage, up to a certain level, both for capital expenditure and for operating expenses. They also reduce the project risk for the industrial partners, mainly in the interface between them. However, the industrial financial contribution is significant, about 1/5 to 1/4 of the total cost. The industrial partners also have full ownership of the installations and operations, and they will retain potentially reduced EU ETS quota costs31. The state aid agreements secure subsidies for CO2 captured outside the EU ETS sector (including CO2 from biogenic sources). In addition, Northern Lights will retain the tariff paid by potential additional, commercial customers.

The initial terms and conditions in the state aid agreements are basically the same for both capture projects. The origin of the CO2 emitted and the regulatory framework governing the emission source are different for Heidelberg Materials and Celsio. This is shown in the table below.

The regulatory framework for the emission source (whether or not it falls under the EU ETS) is relevant to the way in which the state aid agreements are designed. The regulatory framework also affects the emission source’s incentives for CO2 capture. The differences in the origin of the CO2 also affect the capture sites’ incentives for emission reduction. For Longship, which is a demonstration project, it was important to provide the same compensation for all the CO2 captured, regardless of the regulatory framework and origin of the CO2. The state aid agreements therefore included an additional support scheme that will give a similar incentive for capturing non-ETS CO2 compared to the incentives for capturing CO2 under the ETS.

Northern Lights has a different state aid agreement, tailored for transport and storage, and for giving incentives to incorporate new projects. The state aid agreement will cover a large share of the total cost for Northern Lights’ capacity up to 1.5 million tonnes CO2/year. Future revenues will come from the tariff paid by commercial customers for the transport and storage service to be provided. Northern Lights therefore has a strong incentive to develop a commercial market for CO2 transport and storage. 32

| Emission source | Regulatory framework | Emissions based on fossil/biological sources |

| Heidelberg Materials | EU ETS, new combustion tax 32 | 87/13 |

| Celsio | Non ETS/new combustion tax | 50/50 |